The Russian Protective Corps is a unique military formation of the Second World War with its own interesting history, and especially, the uniforms and the insignias. To learn more the reasons for the creation of this formation, you need to study the history of the First World War, the revolution, the White movement, the Red Terror and the Russian emigration. A brief history of the formation of the Russian Corps in the Balkans, military and political background.

First World War Allies of the Entente . The Russian army in the First World War was an ally of France, England and the United States. The revolution made by Lenin with the money of the German General Staff divided Russia into two camps and two armies. The White Army was the former army of Imperial Russia and remained an ally of the Entente during the Russian Civil War. The Red Army fought against the White Army and the Entente countries and dreamed of making a revolution in Europe, in England and even in the USA. The communist system was based on terror, the destruction of the “bourgeois” and the punitive detachments of the Cheka (special services), combined with the propaganda of the ideas of communism.

Under the auspices of France in exile. At the end of the civil war in Russia, the Russian (White) army left the Crimea in 1920, stayed in 1921 at the military bases of the “allies” in Turkey, Greece and Tunisia, then moved to Bulgaria and Serbia. In Bulgaria, the Russian army crushed the communist uprising. In Serbia, the Russians entered the service of the Border Guard. The army switched to a military labor position and worked collectively (in brigades by regiments) on the construction of roads and other engineering structures. Young people with technical education were invited by the Czech government to continue their education and later to work in Czech companies. The older officers left for France, where they worked as drivers for the Russian Taxi. After the evacuation, Russian military schools and cadet corps continued to exist in Serbia to train a young shift of soldiers, fighters against communism and liberate the Motherland from the Bolsheviks. The great writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn wrote in detail about the Red Terror in Russia and the Gulag. The Soviet government not only periodically killed priests, Cossacks, engineers and intellectuals in Russia, but also conducted an active political and armed struggle in Europe with the help of secret operations. Propaganda of the Soviet system and the glorification of Soviet Russia, military and industrial espionage, murders and kidnappings of the leaders of the White movement and the opposition (Trotsky, Ukrainian nationalists, etc.). From the third attempt in 1928, the Commander-in-Chief of the Russian Army, General Wrangel, was killed (poisoned) in Belgium. His deputy, the commander of the 1st Army Corps, General Kutepov, was kidnapped and killed in 1930 in Paris. The next head of the Russian military organizations (ROVS), General Miller, was also kidnapped in Paris in 1937 and killed in 1939 in Moscow on the Lubyanka. With the help of the “Comintern”, combat cells of the hybrid “Army of Moscow” were created around the world from illegal intelligence fighters and legal propagandists. The officers of the Russian army, living in the Balkans, every year dreamed of a “Spring March on Moscow” in order to liberate their homeland from the power of the Kremlin executioners. This went on for many years. The Second World War instilled some hope for a change in the situation.

Hitler’s alliance with Stalin brought disappointment to Russian emigrants, but the war of Germany against the USSR, which began on June 22, 1941, brought hope. Hopes were fueled by the calls of the Russian Orthodox Church, the head of the Romanov Imperial House, the Russian Guard to stand together with the rest of the peoples of Europe in the struggle against the world evil of communism and liberate the Motherland. Hitler concealed his real intentions. The generals of the Wehrmacht and the leadership of the Nazi elite had completely different goals and objectives. Resistance to the Nazi regime grew among the German army and became widely known during the assassination attempt and the failed coup.

Formation of the Russian Corps. After June 22, 1941, communist partisans, led by instructors from the Comintern and the NKVD, began to kill Russian officers of the former Wrangel army and their families, sparing neither old men nor women. To protect themselves, Russian officers under the leadership of General Skorodumov decided to take up arms again and defend themselves from the communist partisans. General Skorodumov created the Russian Protective Corps, but at the same time made unauthorized statements that were unacceptable to the Gestapo. The Gestapo arrested him. Released later, but in protest he refused to lead the Russian Corps. The Russian security corps was headed by General Shteifon, the third official after Generals Wrangel and Kutepov, the former commandant of the 1st Russian Corps in Gallipoli. General Steifon, when communicating with representatives of the German command, immediately set the conditions for creating a corps. The first condition was that the unit was Russian and subordinate only to Russian commanders. The German command will issue orders only through the corps commander. In fact, an army without a homeland, as was the case with the Serbian army in exile. The second condition is that the Russian corps will fight only against its old enemies – the Red Army and Tito’s communist partisans, and never against its former allies – France, England and the USA. The German command agreed with these demands. The corps command sought to send troops to the Eastern Front on a par with the armies of Italy, Hungary and Bulgaria, but given the knowledge of the Serbian language and locality, the German command decided to use them to protect strategic facilities (mines, bridges, roads) and fight against Tito’s communist partisans. Hitler was afraid to send the Russian Corps to the Eastern Front, as it could become a national army. Almost the entire war, the Russian Corps was engaged in the protection of important facilities and communications in Serbia, and only at the end of the war fought against the Red Army, which was already in Yugoslavia. When the KONR (Committee for the Liberation of the Peoples of Russia) was formed in Prague, the Russian corps submitted to General Vlasov.

Uniform. When the corps was formed and within two years, the uniform and weapons were from a combination of 5 countries: Serbia (modified uniform and overcoat), Russia (epaulettes, caps, awards), the Czech Republic (helmets and weapons), the USSR (insignia on buttonholes) and Germany (miscellaneous equipment). After 1943, the uniform became uniform, as in the German army, but with the use of partially Italian uniforms.

There were 5 regiments in total, including the 1st Cossack. The number of about 5 thousand people, in total for all the time there were about 15,000.

Russian Protective Corps in the Balkans 1941-1945

- Structure & Chronology, transport,

- Chronology of the corps, combat operations

- Military training, youth recruiting

- Uniforms, insignia, awards, weapons, small arms, cars and bicycles

- Artillery, types of guns, training and fighting

- Cavalry, horse-drawn gigs, horse transport

- Bunkers, houses, barracks, bridges, combat areas

- 1st Regiment, history, composition, military operations

- 2nd Regiment, history, battles

- 3rd Regiment, history, photos

- 4th Regiment, history, photos

- 4th Regiment of the 2nd formation

- 5th Regiment, history, battles

- Memories: White Army

During the retreat from Yugoslavia to Austria, to the British zone of occupation, the corps surrendered to the British command and was located sequentially in different POW DP camps. Under the terms of the agreement in Yalta, the rank of the corps were not citizens of the USSR for 1939 and were not subject to extradition. Most of the officers had Serbian or Bulgarian passports.

Interesting fact “Disarmed Enemy Forces (DEF)”. After the disarmament of the corps in Austria, the British command issued a certain amount of weapons to maintain order and discipline, as well as repel attacks by red partisans or even NKVD-SMERSH groups. If two Cossack corps and the ROA, consisting of former Soviet citizens, were issued to the Soviets, but the Russian corps from old emigrants was not issued. Later, the corps was transferred to the American zone of occupation in the DP camps, and its ranks emigrated to Latin America and the USA.

DP Camps, emigration and veteran organization. In Europe and then in the USA, the ranks of the corps underwent a thorough check for possible crimes, but both checks at different times showed the “purity” of the service without corpus delicti. In Argentina, the USA and other countries, a legal veteran organization “Union of Alexander Nevsky” was created from the former ranks of the corps, which included partly the ranks of the ROA.

Interesting fact. During the Cold War in 1953, veterans of the Russian Corps living in the United States proposed using the Corps as the basis for the future national liberation army in the war against the USSR. This was the last attempt to create armed units of their emigrants outside the USSR. Children of veterans have already served in the US Army and participated in local wars in Korea and Vietnam.

Later activities of veterans included holding meetings, Orthodox and military celebrations, the requiems, the funerals of members, as well as holding “Days of Remembrance for the Victims of the Fight against Communism” (November 7). In 1999, the organization of veterans of the Corps was officially closed. In this section of the encyclopedia, we will post the above documents and photographs solely to assist historians of the Second World War, including museum workers, filmmakers, collectors, and members of reconstruction groups. Any use of materials for other purposes, including political ones (propaganda of Nazism or Сommunism), may be the subject of legal proceedings and entail administrative and criminal liability. The use of materials in historical research is permitted with written notification of the owners of the archive, the editors of the site and a link to the source of the publication.

Sources, archival materials:

Orders for the Russian Corps 1941-1945.

2. Various documents. Maps, certificates, examples of insignia

3. Photo archives 1941-1941

4. POW and DP documents 1945-1947. Camps Kellerberg and Schleissheim.

5. Photo archive. Retreat, disarmament and DP camps.

6. Chronicle of the corps and each regiment (memo)

7. Memories of the service. Books. Magazine “Our news”.

8. Archive of the veteran organization in the USA and other countries. Photo. Video recordings. Letters, documents

Collection of memoirs by Vertepov D. (New York, USA 1963)

- Russian Protective Corps units last positions map before leaving in 1944, Yugoslavia

- Russian Protective Corps battlefields map in the winter of 1944/1945 and the withdrawal to Austria Alps .

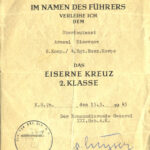

- WW2 German awards for soldiers of the Russian Protective Corps, Iron Cross 2nd class

- Cossack guard at the headquarters building, N1

As a basis for describing the history and plots of the photo gallery, we use an official collection of documents, supplemented by memories not included in the book and our comments.

Russian Protective Corps WW2 Veteran Awards and DP Camp badges

WW2 militaria. White enamel militia cross modeled on the Russian Imperial Army of the First World War. This cross in the white paint was also used on Czech and German helmets of the Russian Protective Corps during WW2. On the cross are the dates “1917-1921” and “1941-1945”, indicating the periods of the white struggle, the “first” and “second” civil wars against the communists and the Red Army. An applied black enamel cross modeled after the camp badge at the French military base at Gallipoli in Turkey. On top of the cross are the letters “P” and “K”, indicating the “Russian Corps”. On the background of the badge there is a crown of thorns, a symbol of the White movement and the beginning of the struggle in the First Kuban “Ice” campaign. The badge in the plastic box was made in Austria or the USA, to be confirmed. A miniature factory (“tailcoat”) badge for wearing on a civilian jacket, a composite one, an invoice, known with two variants of the nut. It is possible that in the DP camps, primitive badges were made by hand using an artisanal method. The price of the badge at auctions is from 50 to 100 dollars. In exile, former ranks of the Russian Corps did not wear military uniforms, with the exception of the Cossacks. Some ranks of the 1st Cossack Regiment of the Russian Corps in the USA continued to wear traditional uniforms and ordered signs of a regular, large size (reference M.B.)

- Russian Protective Corps WW2 veteran award or the badge, A1

- Russian Corps Veterans treasurer and wall badge 2001 photo by M.B., B2

- Wall badge and portrait of the commander of the Russian Protective Corps, B3

- Russian Protective Corps badge certificate, B4

- Kellerberg DP Camp badges, B5

B2 Treasurer of the Association of Former Russian Corps Olga Zavadskaya at the House Museum of the Society of Russian Veterans of the First World War in San Francisco, USA. In the basement, in the dining room, on the wall hangs a large wooden badge of the Russian Corps, as well as a portrait of the commander, Colonel (oberst) Rogozhin. In the oil portrait of the commander of the Russian Corps, Rogozhin, the miniature badge described above is visible. In 2001, there were no real veterans of the First World War left in the Society; the overwhelming majority of members of the Society were ranks of the Russian Protective Corps.

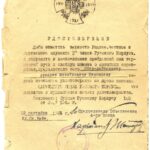

B4 “Certificate. To commemorate the loyalty to the Motherland, the honest sacrificial service of the dignified Russian Corps to it, and to preserve in memory the thorny path they have passed and the bright memory of their fallen comrades, the bearer of this document, Ober-Lieutenant Arkady M. Nizovtsew, was given this certificate for the right to wear the badge of the Russian Corps, which verified by signature and seal.

Reason: Order to the Russian Corps N100 dated July 26, 1945.

September 12, 1945 Klein Sankt-Veit*, for the chairman of the Association of the 4th Haumtmann Regiment (signature and seal of the Russian Corps)”.

*DEF/DP Camp, Austria, before moving to DP Camp Kellerberg in the fall of 1945.

B5 Kellerberg DP Camp badge. In the fall of 1945, in the Kl. St. Veit DEF camp, the Russian Corps was officially disbanded and transferred to the status of the refugees. After this, the Russian Corps was moved to another Kellerberg DP camp, where it remained for the several years before emigrating to Latin America and the USA. Several people emigrated to Australia and France. Everyone who was in the Kellerberg DP camp in 1945 had the right to wear a special badge. In the Kellerberg camp there were also former ranks of the Russian Corps and the other persons. In some sources, this badge is mistakenly called the badge of the Russian Corps instead of the DP Kellerberg camp. The English commandant of the Kellerberg DP camp also received this badge and a certificate for the right to wear it. The badge represents a shield with national colors, with a sword down, the inscription Kellerberg and the date 1945. The first badges were made in the camp using a primitive manual method, then they were ordered to a factory in the USA or Austria, to be confirmed. The price of the badge at auctions is from 50 to 100 dollars (M.B.)