WW2 Photos and photographers of the Russian Protective Corps

Many officers of the former Russian Imperial Army living in exile had experience in amateur photography since the First World War. Portable, compact and inexpensive cameras became a mass phenomenon before the Second World War and were accessible to many. By the time the Russian Protective Corps was formed in 1941, some officers had amateur cameras with small photographic plates or narrow film, allowing them to print photographs at home using contact printing.

According to the memoirs of S. Zabelin*, each regiment of the Russian Corps had several amateur photographers who took photographs for themselves and friends. A study of surviving photographs shows that there were more than a dozen types of camera formats. The best and most affordable were German cameras with excellent photographic lenses from Carl Zeiss. The German command, both on the Eastern Front and in the Balkans, did not prohibit taking photographs for personal purposes, even of strategically important objects. The availability of time off duty and a good salary allowed the officers of the Russian Security Corps to collect collections of photographs of both people and protected objects – railway bridges, mines, transporters, bunkers and barracks. Military parades, holidays, prayer services and training sessions were especially photographed. The command of the Russian Corps had a favorable attitude towards this hobby of its subordinates, as it was in the traditions of the Russian Army. The well-organized evacuation of families from Belgrade and the retreat of the Corps to Slovenia and further to Austria made it possible to preserve all personal belongings and photo albums. Problems began after the disarmament of the Russian Corps and anticipation of further fate in 1945-1947. The nearby 15th Cavalry Corps of von Panwitz and Cossack Stan were forcibly handed over to the Soviet NKVD, where many were killed along the way or died in camps in Siberia. Units of the 1st and 2nd ROA divisions located in Bavaria were also handed over to Stalin. The Soviets also demanded the extradition of the Russian Corps, despite the fact that it consisted mainly of old emigrants. According to the secret agreements in Yalta, the Allies were obliged to hand over not only citizens of the USSR in 1939, but also old emigrants who were captured in German uniforms. Photographs of Russian Corps soldiers in German uniforms became incriminating documents. During the threat of surrender to the Soviets, many members of the Russian Corps destroyed their war photographs in German uniform. For this reason, photographs of the Russian Corps are as rare as those of the soldiers of the Russian Liberation Army of General Vlasov. The changed political situation, the speech of British Prime Minister Churchill in Fulton on March 5, 1946, and the outbreak of the Cold War removed the threat of extradition to the Soviets and allowed former ranks of the Russian Corps to emigrate to Latin America and the United States. The initial and secondary screening of the ranks of the Russian Corps to identify war crimes no longer affected the destruction of the surviving photographs, since twice the international commission recognized that the ranks of the Russian Protective Corps did not commit war crimes and are clean before the law. Beginning in April 1945, Britain and the United States considered plans to use German and Soviet prisoners of war in a possible war against Stalin. Former ranks of the Russian Corps formed the Union of St. Alexander Nevsky as a veteran mutual aid organization. Starting from the DP Kellerberg camp in 1945 and until the end of the 90s, a special magazine “Our News” was published, the official newsletter of the ranks of the former Russian Corps. The long-time editor of this magazine, Nikolai Protopopov, collected a large collection of surviving photographs from the Second World War. Two more collections of photographs were collected by the Chairman of the Union of Officials of the Russian Corps, Lieutenant Wladimir Granitow, and the head of the Museum, Peter Gattenberger. Unfortunately, there was no correct attitude towards collecting and storing photographs. Another head of the museum, Svyatoslav Zabelin, did not pay due attention either. According to his confession, many times and for many years he wanted to come to visit one photographer who kept both negatives and photographs, but constantly postponed the trip. And at one point he learned that the photographer had already died, and all his personal belongings and negatives were destroyed in accordance with US laws. In the 90s, while the last veterans of the Russian Corps were still alive, Mikhail Blinov, editor of the magazine of the Society of Russian Veterans of the Great War in the city of San Francisco, was also searching for and collecting surviving photographs. When receiving photographs, important information was also recorded – the place and time of photography, what event was shown and the names of the soldiers. This is how a photo collection was formed, which is posted below along with the original signatures and comments of Mikhail Blinov. The main blocks of photographs are: the official photo archive of the Russian Corps with a stamp, the collection of cadet Vadik Vasiliev from the 3rd regiment, Peter Gattenberger, Andrei Sergeevsky, Jan Eilert and other veterans of the Russian Protective Corps. A collection of photographs of the Cossack Stan and the Russian Liberation Army will be published separately.

We place topographic maps, documents, IDs, uniforms and insignia, the structure of the Russian Protective Corps and a description of the battles during the Second World War in our special Guide.

- WW2 Russian Protective Corps Guide books, battlefield maps and description

Official photo archive of the Russian Protective Corps

The placement of photographs into sections is made for ease of study and will change over time as more information becomes available. Many photographs are published for the first time.

- “Belgrade 1941”, cadets with machine guns and a dog (B61)

- “8th Artillery Hundred in Mitrovica” (? 1942, B81)

- Hundred commander and officers, fragment 81

- Uniform 1942, shoulder straps of an artillery colonel (WWI) and oberleutnant’s buttonholes (Russian Corps), L1

B61 A nice photo, but small in the size, showing the variety of uniforms during the first two years. WW1 Russian field tunics with the pockets, shoulder straps, caps, trousers, sapogi and boots.

B81 Pay attention to the awards and badges of the military school of the Russian Imperial Army. The badge of Gallipoli or Lemnos is also visible.

Ibr river valley and mountains: Rahove, Kosovska Mitrovica, Zvecan, Rudnica, Raska.

Bunkers and guard posts along the highland teleferik line. Photo gallery from the album of Vadik Vasiliev and his father. Official signatures on the photographs, as well as supplemented notes by Michel B. from Vasiliev’s words in pencil on the back of the photo and audio files of the story. Later, in 1944, the Ibr River valley became the bloody battlefields with the Red Army and Tito’s partisans.

- In the mountains of the Rahove valley, B48

- Ground position socket type (?) B44

- The famous air line from Zvecan to Rahove, B42

- “Travel from Rahove to Kosovo Mitrovica” B43

- “Trip Rahove – Mitrovica 8th hundred of 3rd regiment, artillerymen are moving to position” (N B40)

- Transition from Post N20 to Rudnitsa (?Germans) B41

- Voivode Stepa, BB11

- Bridge over the Ibr River, B28

- Kosovo Mitrovica city, river valley and mountains, BB10

- Epiphany parade in the winter of 1943/1944 near the barracks in Kosovo Mitrovica, BB15g

- Training of the 8th artillery hundred of the 3rd regiment in the Ibr River valley, 1943, B7

- “Rashka, hitching post” (horse parking) N B39

B42 “Transition from Rahove to Kosovo Mitrovica” (official text, comments by cadet Vasiliev under the photo), 1942. Pay attention to the mini-bunker, the guard post under the tower.

B44 “Rahove, air line”, “8th artillery hundred 3rd regiment”. A village in the valley and mountains are visible in the distance; perhaps the post was used as an observation post and fire adjustment.

Jošanička Banja the famous resort, Rashka area

- “View towards Voed Stepa and Karlocha”, B36

- Railroad station Jošanička Banja resort, B29

- In summer sports uniform in the garden with tokens, B32

- Beach on the Ibre River near the chapel, B37

- Beach near the bridge over the Ibr River and the bunker, B38

- Therapeutic and prophylactic mud at the resort, B30

- Commander of a hundred in a hybrid German and Russian uniform, B34

- Bridge and bunker near Jošanička Banja resort, B53

- Artillery firing, B54

- close-up view of the weapon, B51

N B36 Steam locomotive and carriages near the railway station, 1942 or 1943.

Photo B37, the ranks of the 8th artillery hundred of the 3rd regiment of the Russian Security Corps are swimming on the beach on the Ibr River. The chapel was converted from a mill; prayer services took place there.

B34 The commander of the 8th artillery hundred of the 3rd regiment, Colonel Murzin and his son in a hybrid German and Russian uniform.

Bor mine area.

- Valley and mountains, N L03-10

- Bunker N6 in the Bor mine valley, MB L03-08.

- Valley and barracks in the distance, L03-12

- German and Russian barracks, railway and bridge, L03-9

- View of the bunker from the southwest, N L03-03

- On the dome of the N6 bunker, embrasures, L03-5

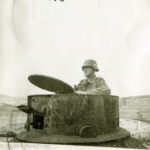

- Armored turret on the bunker dome, L03-7

- Peter Gattenberger in a helmet with binoculars, L03-6

Drina River valley and surrounding mountains

Stolice kod Krupnja. the important mine in a valley among the mountains

- Panoramic view of the Stolice from above, “Goat Wall”, BB16a

- Mountain road from Stolice to Loznica, B62

- Barracksi n summer , BB16b

- Russian sentry near the barn, Stolice, B59

- “Evening Prayer” In the foreground is Second Lieutenant Granitov., B60

Ljubovija city area (Drina River valley)

Historical area and the famous WWI battlefileds between the Serbian and Austro-Hungarian armies. On the map of Serbia it is located south of Stolice and Zvornik, in the valley of the Drina River.

- Ljubovija city, platoon commanders on bicycles, BB13g

- First promotion to officer rank near the church, BB13b

- Orthodox priest presents an icon to the 1st hundred, BB13v