Photo: A monument on the site of the former fortress-prison, destroyed by the Parisian “communards” as a symbol of the “oppression of the working people”

The area named after the capture by the Parisian Communards of the stronghold of the world oppression of the working people of the fortress-prison of the Bastille 🙂

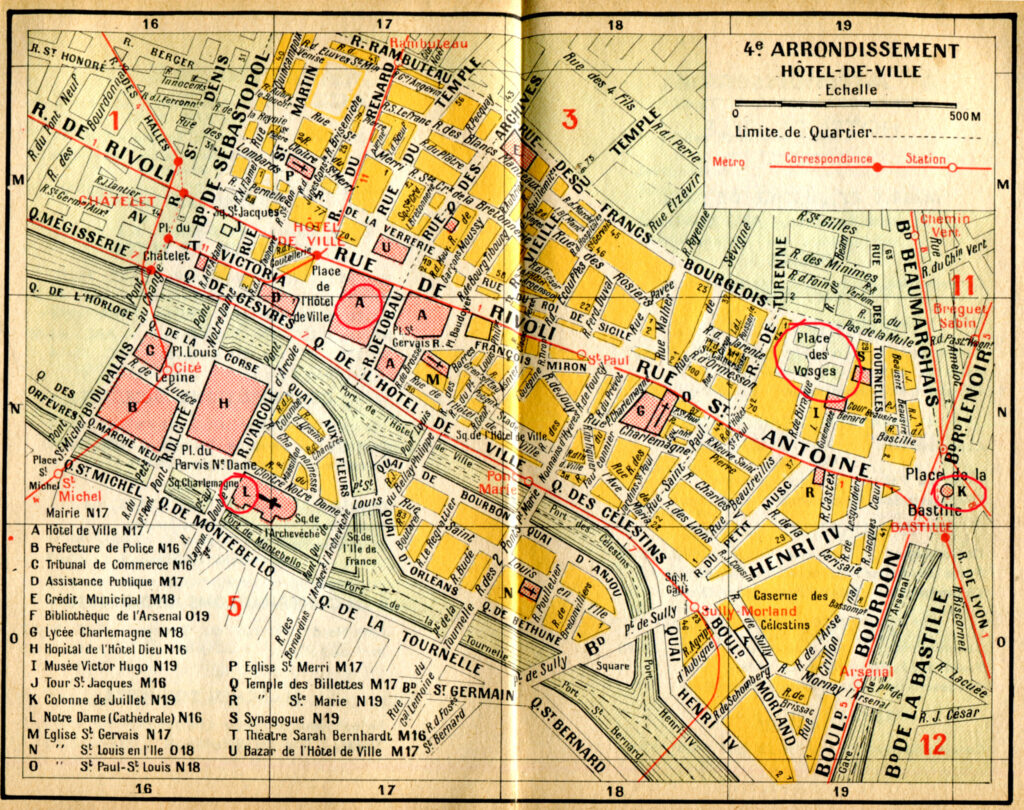

Bastille Square (French la place de la Bastille) is a square in Paris that owes its name to the Bastille fortress, destroyed during the French Revolution. It is the intersection of more than ten streets and the boulevards.

Fortress Bastille. At the beginning of the French Revolution on July 14, 1789, the fortress was taken by the revolutionary-minded population. It took three years to dismantle the fortress. From house number 5 to house number 49 along Henry IV Boulevard, a line was laid out with paving stones, which indicates the contours of the walls of the destroyed fortress. A sign was placed on the wasteland with the inscription “Désormais ici dansent”, which means “From now on, they dance here” and every year folk festivals began to take place here. The tradition is still preserved.

July column. In 1833, Louis Philippe I decided to erect the July Column in the square in memory of the “three days of glory” from July 27 to July 29, 1830 during the July Revolution. Its opening took place in 1840.

Today, various concerts, fairs, marches are held on the square, this is the starting point for many demonstrations – political, trade union, May Day and others. Parisian youth gather here in numerous cafes, restaurants and nightclubs. On July 14, the largest Parisian ball is held here.

Interesting Facts. Once upon a time, Napoleon wanted to erect a giant monument elephant in honor of his Egyptian campaigns on the site of the Star Square. instead of the Arc de Triomphe. The idea did not pass (well, it’s not nice for his troops to walk between the legs of an elephant, and even under the “interesting” organs of the body. A huge model of the monument was built from wood and plaster.

But there was an elephant in Place de la Bastille. The Directory placed the model of an elephant on a pedestal plate. Readers in Russia know about this from Victor Hugo’s novel about Gavroche. As it is written in the novel, rats lived in the elephant in Place de la Bastille and the boy Gavroche spent the night. When the elephant fell into complete disrepair, it was dismantled and the column that we see now was installed.

The history of the fortress-prison of the Bastille.

Bastille (historical name – le Bastille Saint-Antoine) was originally one of the towers in the east of Paris. It existed already in 1358. It began to be built as a fortress on April 22, 1370. It began to function in 1383. It was a rectangle with walls 8 m high and 3 m wide, 8 towers, 2 courtyards, a wide (25 m) moat deep 8 m, with a gate facing the Saint-Antoine suburb, a drawbridge for the passage of horses and carts, and a narrow drawbridge for the passage of people. By 1382, the fortress already had the same appearance as in 1789. During various unrest and uprisings, kings with their retinue periodically hid behind its walls.

At the same time, a rich monastery was located on the territory of the fortress, called the “Pious St. Anthony’s Royal Castle.” In 1471, King Louis XI granted the monastery enormous privileges and issued a decree that local artisans should no longer be subject to guild laws. This was the heyday of the Saint-Antoine suburb of Paris, the artisans of which were the first to rebel in 1789, and it is the taking of the Bastille that is considered the beginning of the French Revolution at the end of the 18th century.

From the beginning, the Bastille served as a prison for state criminals. They imprisoned here at the will of the king without trial or investigation. The first prisoner was the architect of the Bastille, Hugo Obrio, who was released by the crowd 4 years later (in 1381). In the Middle Ages, the French commander Antoine de Chabanne (1408-25.12.1488) was kept here; Jacques d’Armagnac, Duke de Nemur (1433 – 08/04/1477), accused of plotting against the king and imprisoned in an iron cage; constable of France Louis de Luxembourg (1418 – 12/19/1475). In the era of religious wars, the prisoners were: the president of the Parisian parliament, Achille d Arles (03/07/1536 – 10/23/1616). French marshal Francois de Montmorency (July 17, 1530 – May 6, 1579), writer and philosopher Michel de Montaigne (February 28, 1533 – September 13, 1592). At the end of the 16th – beginning of the 18th centuries. in the Bastille there were such famous prisoners as the 3rd Prince de Condé Henry II (1.9.1588 – 26.12.1646), one of the main participants in the Fronde; Marshal of France Francois de Bassompierre (April 12, 1579 – October 12, 1646), the mysterious prisoner of the “Iron Mask” (circa 1640 – November 19, 1703), whose real prototype was a certain Eustache Dauger, who wore not an iron, but a black velvet or silk mask; Superintendent of Finance Nicolas Fouquet (January 27, 1615 – March 23, 1680); marshals of France Francois de Montmorency-Boutville (January 8, 1628 – January 4, 1695) and Louis Francois de Richelieu (March 13, 1696 – August 8, 1788), great-grandnephew of Cardinal Richelieu; writer and freemason Jean-Francois Marmontel (11/07/1723 – 31/12/1799); philosopher – educator, historian, publicist, poet and prose writer F.-M.-A. Voltaire (11/21/1694 – 5/30/1778); playwright and publicist P.-O. C. de Beaumarchais (January 24, 1732 – May 18, 1799); Cardinal L.R.E. de Rohan-Gemene (September 29, 1734 – February 16, 1803); mystic and adventurer Alessandro Cagliostro (Giuseppe Balsamo, 2/6/1743 – 26/8/1796); politician, philosopher and writer Marquis D.A.F. de Sade (2.6.1740 – 2.12.1814); adventurer Madame de Lamotte (J. de L. de Saint – Remy, 22.7.1756 – 23.8.1791); Portuguese Catholic monk abbot J.K. Faria (May 31, 1756 – September 20, 1819) and others. Twice (in 1753 and 1756) the publicist L.A. de Labomel (January 28, 1726 – November 17, 1773).

One of the most famous commandants of the Bastille was Brigadier General Francois de Montlezen de Bezmo (1654 – 12.2.1697), a colleague (in the guard company of Captain Dezessar) Charles de Batz de Castelmore, Count d’Artagnan …

It is interesting to note that even before the revolution, in 1784, the Parisian city architect Corbet presented a plan for the demolition of the Bastille, which had practically lost its significance, and the creation of the Royal Place Louis XVI in its place. But then it could not be implemented.

By mid-July 1789, unrest among the masses reached its climax. On July 12, in the Palais Royal, in front of a crowd of 60,000, the famous publicist and journalist Camille Desmoulins delivered an incendiary speech in connection with the resignation of Prime Minister Necker, the main leitmotif of which was the words “Citizens, to arms!” On the same day, soldiers of the French Guard regiment joined the Paris mob.

July 13 was followed by the decision of the Standing Committee of the Parisian electors in the Estates General to form in the city of Paris “Civil Guard” – i.e. National Guard. She needed weapons and the mob ransacked the Arsenal in Paris. On the morning of July 14, the Parisians gathered in Les Invalides seized 32 thousand guns and a number of guns. However, gunpowder was clearly not enough. An armed mob led by P.-O. Gülen and J. Eli (an officer of the Queen’s infantry regiment), with 5 guns, went to the Bastille, where, according to rumors, a lot of gunpowder and guns were stored to arm the volunteers. In addition, the guns of the fortress could fire on the Saint-Antoine suburb. The Standing Committee had no serious intention of storming the Bastille, it was only necessary to take gunpowder and move the guns away from the embrasures.

The garrison of the fortress under the command of the commandant of the Marquis Bernard-Rene Jordan, Marquis de Launay (8 or 9.4.1740 – 14.7.1789) consisted of 32 infantrymen of the Swiss regiment of Saly – Samand, 82 invalids and 15 (according to other sources 30) guns …

On July 14, there were only 7 prisoners in the Bastille: 4 counterfeiters, 2 lunatics and 1 murderer. After taking it, they were all released and carried in triumph through the streets of Paris …

The delegation from the municipality, sent to de Launay at about 10 o’clock in the morning, offered him to surrender the fortress and the arsenal located in it, but he flatly refused and ordered the guns to be moved away from the embrasures. Then attorney-at-law Thurio went to de Launay from the inhabitants of the Faubourg Saint-Antoine and noted that the guns had already been removed from the embrasures. De Launay told him that in “the case of a peaceful resolution of the situation.” Thurio left the Bastille half an hour later, but two of the rebels were able to climb onto the drawbridge and lower it. The crowd burst into the courtyard and de Launay ordered to open fire. In response, the crowd also began to shoot.

At about 3 pm, a detachment of soldiers of the French Guard regiment and national guardsmen with 5 guns under the command of Gülen approached the fortress and its attack began. Covered by the smoke of burning straw wagons, the guns under the command of Eli were directed from three directions at a large drawbridge. After two hours of artillery fire, a white flag was raised over one of the towers, and a note was slipped through the crack in the gate. To get to it, a board was thrown over the ditch, but the first one who tried to go along it broke and died. The second, the bailiff Stanislav Mayer, managed to safely cross the ditch and take the note. She was read. It said that de Launay wanted to blow up the fortress if the honorable terms of surrender were not accepted by the besiegers. In response, the attackers opened fire again.

De Launay did not rely on armed support from Versailles and therefore, remaining true to his oath, decided to blow up the fortress with the help of wicks in a powder magazine. However, the defenders did not want to die, and non-commissioned officers Bekkar and Ferrand took away the torch from him and forced him to immediately convene a military council, which almost unanimously decided to surrender the fortress. The defenders lowered the large drawbridge and the rebels broke into the courtyard of the Bastille. This happened at 4:40 p.m.

Gülen and Eli guaranteed the safety of those who surrendered, but the angry crowd immediately hanged 3 officers, 3 soldiers and the merchant foreman of Paris Flessel (he was killed for giving the rebels boxes of rags instead of boxes with guns; his head was hoisted on the peak). The defenders of the fortress lost 1 disabled person killed, and the rebels lost 98 (or 83) people killed and 73 (or 88) wounded. De Launay was captured and was scheduled to be taken to the town hall for trial, the outcome of which was already a foregone conclusion. However, passing through the Greve Square, he hit one of the rebels in the groin (it turned out to be, according to some reports, an unemployed cook), after which he was picked up on bayonets and dragged to a ditch, where the cook cut off his head; then she was put on a pike and carried for a long time through the streets of Paris. De Launay’s body was never found. The bodies of the hanged officers were taken to the morgue.

The storming of the Bastille became a symbol of the fall of the absolutist regime in France. When the king was informed about the events in Paris and the taking of the Bastille, he exclaimed: “But this is a rebellion!” The Duke of Liancourt, who was present here, objected: “No, sir, this is a revolution!”.

The next day, massacres of aristocrats began in Paris, which caused their mass exodus from the city and the further emigration of some of the surviving nobles.

On July 15, it was officially decided to destroy the Bastille and immediately began work on its destruction, which finally happened on May 16 (according to other sources, 21) May 1791. In its place, the demolition contractor installed a sign with the inscription “From now on, they dance here.” Most of the fortress stone blocks went to the construction of the bridge of Louis XVI (later – the bridge of the Revolution, now – the bridge of “Consent”). The stones of its walls and towers were sold at auction for 943,769 francs. From broken stone, one craftsman made miniature images of the Bastille and sold them as souvenirs. The archive of the fortress was plundered during its capture and only a part of it has survived to this day.

Who was directly involved in the storming of the Bastille? There are 3 known lists of “winners of the Bastille”. In one there are 871 people, in the other – 954, in the third – 662. The latter was compiled by S. Maillard, but although it is incomplete, it contains indications of some professions: guardsmen and soldiers – 77 people, merchants – 4, employees – 5, teacher – 1, apprentices and workers – 149, artisans and shopkeepers – 426 people.

In August 1789, the establishment followed, and on September 1, the decree of the medal “To the Victor of the Bastille” . She was in the form of a rhombus with balls at the ends; on the front side there was an image of a sword, pointing upwards, piercing a wreath, on the back – lying chains and an open lock. A total of 850 were issued; 104 medals were received by the French guards. However, due to the almost universal disgust at the very principle of awarding orders and medals, many who were awarded it returned and it had to be canceled. In addition, a chest ribbon, stretched down, with the inscriptions “July 14, 1789” and “Volunteer of the Bastille” was also established. There was also an oval medal with a different design, also worn on a ribbon.

A year after the storming of the Bastille, on July 14, 1790, in order to celebrate this event and the established reconciliation between the king and the people’s representatives, a holiday was arranged, organized by General Marquis de Lafayette. He also handed over one of the keys to the Bastille to General George Washington, and he is now kept in the museum – the presidential residence of Mount Vernon.

In 1792, General Bonaparte proposed to build a fountain in the empty square in the form of a giant war elephant with a turret on top, which were used in ancient armies. However, due to objective circumstances, this was not possible at that time. Instead of an elephant, in 1793, the so-called “Renaissance Fountain” in the Egyptian style was mounted on Freedom Square – a woman from whose breasts water jets flowed. It was dedicated to the capture of the royal palace of the Tuileries in 1793.

Only in the period of the First Empire, in 1808, the idea of an elephant was returned again, but instead of a bronze elephant cast from remelted trophy bronze guns in 1813, a wooden 24-meter model of the monument was installed, which was immortalized in Victor Hugo’s immortal novel Les Misérables (Gavroche spent the night inside it). Over time, the elephant practically fell into disrepair, but stood until 1846 (or 1848).

After the July Revolution of 1830, in 1833, King Louis Philippe ordered the installation of the so-called “July Column” in the square in memory of the “three glorious days” – July 27, 28 and 29, 1830, as a result of which he ascended the throne. On July 28, 1840, a bronze column 50.5 meters high was unveiled, the top of which was crowned with the statue of the “Genius of Liberty” by Auguste Dumont, at the base there were Bari bas-reliefs. At the base of the column is a crypt with the remains of 504 victims of the July Revolution and about 200 remains of those killed during the 1848 revolution.

On July 6, 1880, the date of the national holiday was chosen. The choice fell on the anniversary of the day of reconciliation – July 14, 1790, but not on the date of the storming of the Bastille.

Today, Place de la Bastille is located: a junction of three lines of the Paris metro, the new building of the Paris Opera and the intersection of a dozen streets and boulevards.

PS Not far from here begins the historical part of the Marais quarter.