Musée du Louvre is one of the oldest museums in the world with a huge collection of artistic and historical relics of France, from the time of the first Capetian dynasty to the present day. The Louvre Museum collects artifacts from all over the world and from every historical period, forming a universal and worldwide collection. The Museum’s collection spans vast geographical and temporal spaces: from Western Europe to Iran, Asia to Greece, Egypt, and the Middle East. It can confidently be called the foremost museum of world history, culture and art. The Louvre is also the most famous museum in the world, visited by over eight million people a year.

Before we discuss the museum’s collections, we must first answer a simple question. What is the Louvre? There’s a rather complex answer.

Paris in the 12th century was still a small city, built on top of the former Roman and Gallic settlement of Lutetia. France was governed by an array of feudal kings and princes, some loyal to Paris, some to London, and others independent. Due to this, in 1190 the Kingdom of France’s western border lay right outside of Paris. Beyond it was the duchy of Normandy, which was at the time English. Before he left for the Third Crusade, King Philip Augustus built a small fortress here to protect against the English. According to the traditions and necessities of the era, royal treasures and valuable papers were secured in the well-protected fortress while he went on crusade. These treasures can be considered the first collection of the Louvre.

In 1317, the royal treasury was also transferred to the Louvre for safekeeping. A little later, under Charles V, the fortress was renovated into a true royal palace, adding luxurious elements to what was once a primarily martial interior. The Louvre’s original fortifications have been excavated several times in the modern era, and the remaining walls are on display in the basement level.

During the Renaissance, a major restructuring of the palace took place, while the architects fulfilled the wishes of two kings – Francis I and Henry IV. In 1528, Francis I ordered a major renovation project, starting with the destruction of the obsolete Great Tower, the old keep. With the victories of the French crown over the English in the Hundred Year’s War, the fortifications on the Seine were unnecessary – England had been booted off of the continent, its holdings in France conquered.

In 1546 the transformation of the fortress into a magnificent royal residence began. Unsatisfied with traditional medieval stylings, Francis I commissioned a reimagining of the palace in the new styles of the Renaissance sweeping Europe. The main part of the fortress wall was destroyed, and a huge gallery was built connecting the Louvre and the Tuileries Palace. However, Francis I died in 1547, barely a year into the project, but his successor Henry IV would resume the project in 1549. The overhaul was carried out by architect Pierre Lescot, continued during the reigns of Henry II and Charles IX, and ultimately added two new wings to the building. One wing still survives today as the aptly named Lescot Wing, the only Renaissance era structure to survive on the grounds of the Louvre.

King Henry IV was not only the king of France, but also a great art collector. At the beginning of the 17th century he sponsored promising artists to live and work in the palace, so as to produce great works of art for the royal collection under his patronage. Artists were allocated spacious premises for workshops and accommodation, and the masters among them received a special prestigious status as painters of the royal court. From this time on, the Louvre turned into a large royal art gallery. The square courtyard of the palace was created by the architects Lemercier, and then Louis Levo during the reigns of Louis XIII and Louis XIV, enlarging the palace fourfold. The design and decoration of the palace was then supervised by such artists as Poussin, Romanelli and Lebrun.

Between 1667 and 1670 the architect Claude Perrault built the Louvre Colonnade on the eastern façade of the palace, facing the Louvre Square. However, Louis XIV preferred his residence outside of Paris, at Versailles, and by the late 1670s work on the Louvre was suspended as the King had since left the palace for good. Louis XIV would be the last king to remain in residence at the Louvre for any significant amount of time.

With the king gone to Versailles, the Louvre was suddenly left as a royal residence without a royal family. However, the building held artists, authors, and sculptors in abundance, and these types availed themselves of the space to give the palace new purpose. Famous artists, sculptors, and architects such as Jean Honore Fragonard, Francois Boucher, Jean Chardin, Jean-Louis David, Guillaume Coustou, continued to live and work in the Louvre. However, the Louvre was a fantastically expensive building to maintain, and without the pressures of the royal court, the buildings themselves fell into disrepair around the artists. It became so bad, that by the 1750s a third of the palace was deemed “roofless and uninhabitable”, and there was a proposal to demolish the complex in favor of the neighboring Tuileries Palace.

The French Revolution of 1789 did not cause damage to the buildings, probably due to their status as an artistic compound of unclear status, and the decades of separation from their original role as the monarchy’s residence. Ironically, while it once seemed that the monarchy’s move to Versailles would doom the Louvre, it was this disassociation with the hated king in the 1790s that likely preserved it. The Louvre was declared a public state museum for the Arts and Sciences, and opened to the public three days a week – a major change from the previously sequestered audience of royals and artists it once exclusively catered to. Renovation at the Louvre, now the Central Museum of Arts of the Republic, was continued by Napoleon I.

The new Emperor Napoleon was eager to display the thousands of pieces of looted art captured by his forces on his behalf on campaigns across Europe in the Napoleonic wars. Spanish, Italian, Dutch, and Greek artworks flowed into the Louvre through war and treaty. His architects Percier and Fontaine began the construction of the northern wing along the Rue de Rivoli. Later, Napoleon III fulfilled the dream of King Henry IV and in 1852 added the “Richelieu Wing” to the Louvre, which became a symmetrical reflection of the existing gallery. The Paris Commune and its communards, according to revolutionary traditions, simply burned down the Tuileries Palace in 1871, as well as part of the Louvre, but severe damage was thankfully prevented due to the efforts of Parisian firemen and the museum’s own curators.

The museum went through cycles of display and renovation in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. Famously, the collection was evacuated in three days at the start of World War II, and smuggled from chateau to chateau during the German occupation to prevent its plunder. These extraordinary efforts were largely successful, and few works of art were pillaged from the Louvre than compared to other, less fortunate museums in occupied Europe.

The 1980s saw the largest restoration and renovation project for the Louvre since the days of Napoleon. Under President Mitterand, the French finance ministry was ejected from their side of the Louvre complex, every gallery refurbished, and the museum’s focus expanded to encompass art from all over the world, not just western civilization. Much controversy arose over the new construction, including the now-famous glass pyramid erected in the center of the Napoleonic courtyard in 1989, designed by architect Yo Ming Pei. Today, the Louvre’s collection includes more than 350,000 artifacts from around the world, and the museum employs almost 1,600 people, including security and caretakers.

Louvre museum. The Galerie d’Apollon, created over two centuries to glorify the Sun King, Louis XIV, and his majesty.

Collection of the Louvre Museum

On August 10, 1793, during the French Revolution, the doors of the museum were first opened to ordinary people, and under the First Empire it became known as the Napoleon Museum. At the beginning of its existence, the Louvre exhibited from the royal collections collected at one time by Francis I (Italian paintings) and Louis XIV (the largest acquisition was 200 paintings by the banker Everhard Jabach). At the time of the museum’s founding, the royal collection numbered exactly 2,500 paintings. Gradually, the most valuable paintings of the royal collection were transferred to the museum’s collection. A huge number of sculptures came from the Museum of French Sculpture (musée des Monuments français) and after numerous confiscations of property during the revolution. During the Napoleonic wars, at the instigation of the first director of the museum, Baron Denon, the Louvre collection was replenished with military trophies, and at the same time the museum received archaeological finds from Egypt and the Middle East. During the 19th and 20th centuries, the museum’s collection was expanded as a result of many acquisitions and gifts, including the latest – the collection of Edmund Rothschild, which was inherited by the museum according to his will.

Other exhibits came to the Louvre in various ways. The famous paintings of the Louvre – “La Gioconda” by Leonardo da Vinci and “La Belle Gardener” by Raphael – belonged to Francis I, who acquired Leonardo’s personal collection after his death in 1519. Many paintings ended up in the Louvre as trophies of the Napoleonic army, especially after the sack of Venice in 1798 (for example, “The Marriage at Cana of Galilee” by Paolo Veronese). “The Little Beggar” by Murillo was purchased by Louis XVI in 1782. “The Lacemaker” by Vermeer and “Self-Portrait with a Thistle” by Dürer were acquired by the museum in 1870 and 1922, respectively. Finally, the painting “Christ on the Cross” by El Greco went to the museum for free, as it was taken from the courthouse in Prades (Eastern Pyrenees) in 1908.

The most famous sculptures of the museum are the Venus de Milo, rediscovered in 1820 on the Greek island of Milos and then acquired by the French ambassador from the Ottoman Turkish government, and the Nike of Samothrace, found in parts in 1863 on the island of Samothrace by Charles Champoiseau, an archaeologist and vice-consul of France in Adrianople. The Louvre collections contain masterpieces of art from different civilizations, cultures and eras. The museum has about 300,000 exhibits, of which only 35,000 are exhibited in the halls. Many exhibits are kept in storage because they cannot be shown to visitors for more than three months at a time for security reasons.

Mini-Guide to the Collections

The main collections are located in three wings of the building: Richelieu (along the Rue de Rivoli), Denona (parallel to the Seine) and Sully (surrounding the square courtyard). A quick description of where everything is located:

— The Ancient East and the art of Islam are located in the Richelieu Wing (ground and first floors) and in the Sully Wing. Objects of ancient art found in the territory from the Bosphorus to the Persian Gulf, Mesopotamia, Persia, the countries of the Levant. The “Ancient East” section was founded in 1881 and contains one of the richest collections in the world, telling about the heyday of Assyrian art in the 9th-7th centuries BC, artifacts from ancient Palestine, Tunisia and Algeria. Some of the oldest and earliest of artwork known to exist are on display.

— Ancient Egyptian art is located in the Denon Wing (ground floor) and Sully Wing (1st and 2nd floors). The exhibition shows ancient Egyptians – papyri, stuffed animals, sculptures, mummies, columns, fragments of temples, paintings, talismans, in total more than 55,000 exhibits, arranged in chronological order.

– Ancient Greek, Etruscan and Roman art can be found in the Denon Wing (ground floor) and in Sully (1st and 2nd floors). A collection of artifacts from areas inhabited by the ancient Greeks, Etruscans and Romans includes the main sculptural attractions of the Louvre – the Venus de Milo (100 BC), Apollo and Nike of Samothrace (found in the form of 300 fragments a thousand years after its creation). Greek and Roman jewelry is of particular historical, cultural and material value.

— Decorative and applied arts occupy the Richelieu Wing (2nd floor – apartments of Napoleon III), the Sully Wing (2nd floor), and also the Denon Wing (2nd floor). Various artifacts from the throne of Emperor Napoleon I to tapestries, treasures from the Basilica of Saint Denis: jewelry, antique furniture, carpets, antique weapons, snuff boxes, glass, porcelain, bronze, ivory and wood, collection of miniatures, porcelain, fine bronze and even royal crowns.

— Sculptures are located in the Richelieu Wing (ground and 1st floors) and Denon (ground and 1st floor), showing a collection from France, exhibits from Italy, Germany, Holland and Spain, including two works by Michelangelo.

— Paintings are located in the Richelieu Wing (3rd floor) — French schools of the 14th-17th centuries, Dutch, Flemish and German. In the Sully Wing (3rd floor) there are French paintings of the 17th-19th centuries, in the Denon Wing (2nd floor) there are large format paintings from 19th century France, Italian and Spanish painting.

The famous “Mona Lisa” (“La Gioconda”) by Leonardo da Vinci himself is located in the Denon Wing, in the Great Gallery of Hall No. 6, always surrounded by a huge queue of people.

– The Graphics and Prints are located in the Richelieu Wing (3rd floor) – northern schools, in the wing. Sully (3rd floor) – French school, Denon (2nd floor) – Italy. The main attractions, of course, are the drawings of the Great Master himself, Leonardo da Vinci, the Moroccan album of Delacroix, as well as sketches by Rembrandt and more, in total more than 120,000 works.

— The Medieval Louvre in the Sully Wing on the ground floor showing the history of the museum complex, fortress, palace and buildings, excavated and restored in the 1980s.

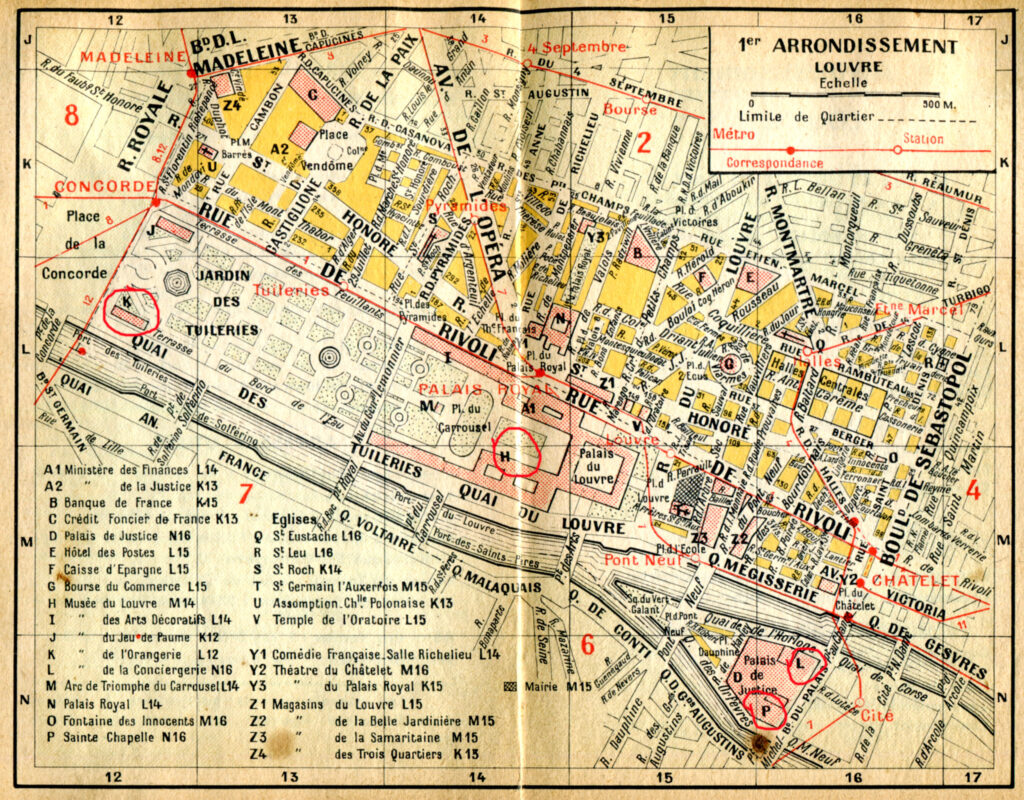

The museum complex is located in the very center of Paris, on the right bank of the Seine River, on Rivoli Street, in the 1st arrondissement of the capital and is indicated on all modern and old maps of the city.

Louvre Museum, Tuileries Garden, Place de la Concorde at the center of of this historical map of Paris

My Personal Experiences of the Louvre Museum

For 25 years now I have been traveling to Paris and France, but to my shame, I had never before been to the Louvre, preferring the military and technical museums of the First and Second World Wars. I decided to visit the Louvre Museum quite by accident and spontaneously, after watching the movie “The Da Vinci Code”. The magnificent performance of the French actor Jean Renault (Police Captain Foch) in the large Louvre galleries on film with a slightly fictitious but interesting story accelerated my visit to the best museum in the world. But long queues at the Louvre reduced the desire to visit, since there are too many people interested at any time of the year from all over the world. (The Louvre is the most popular museum in the world by a wide margin.) For tourists, Monday is the worst day, as almost all museums are closed. Almost everything, since the Louvre and a handful of other museums are the few exceptions. Walking through the Tuileries Gardens in the morning on Monday, September 3, 2018 I accidentally discovered that the queue to enter the Louvre near the Pyramid was of average size, not very huge. The decision came quickly and spontaneously – to stand at the end of the line and seek to learn the basic layout and history of the Louvre.

To carefully study all the exhibitions of the Louvre, you need to visit the museum fifteen or more times, so the goal was precisely a sightseeing tour. For an overview tour around the Louvre Museum, it is better to use a licensed guide, an expert in the field of art, but guides must be booked several days in advance. An individual tour with a licensed guide allows you to save time, since you can visit the Louvre without a queue and, of course, a fascinating story from a specialist. For independent visits, there are audio guides in different languages and excellent maps of the location of the collections in the halls and wings of the huge complex of buildings.

After standing in a short queue, purchasing an entrance ticket and receiving a free map of the halls, I began to examine the collections. There was no time to study the map, so I chose the easiest way – to go around the halls counterclockwise, floor by floor, so that in the evening I could study the route I had taken. I came across Donatello’s Italian gallery of sculptures from the 6th to 13th centuries first, followed by marble sculptures and bas-reliefs of Holy Warriors from the 14th century from Constantinople. This was a pleasant surprise, since I know old Constantinople and modern Istanbul very well and sometimes even conduct special tours to memorable places of the First World War and military history.

After the corridor, a large hall became visible with many marble sculptures from the 10th to 15th centuries with images of Jesus Christ, St. Mary, angels and scenes from the Bible. Some sculptures were made especially for chapels and churches by famous artists, mostly Italian. The religious scenes and individual figures of various scales from Florence seemed very beautiful, colorful and well preserved to me. In the photo gallery below I post some photos of sculptures that I liked. Photography, of course, is not professional; besides, glass, reflection from windows and lamps do not allow you to take good photographs, but they allow you to show beautiful exhibits. (The Louvre is kind enough to provide high-quality scans of their artworks for free on their website.) Next there was a staircase with a branching path, but I chose the logical continuation – a hall of sculptures of Northern Europe, Germany, Holland of the 15-16th centuries… Again beautiful sculptures on religious themes, again Christ the Savior, scenes from the Bible, cardinals and Popes, made as if from stone , and from valuable woods. The presence of alabaster in these regions influenced the choice of material. I immediately remembered the trips from Paris to the north, to the Alabaster Coast, Etretat and the cliffs, the amazing nature. After covering the late Gothic and St. Catherine, staircases lead to different sections and directions of exploration. After looking at masterpieces on a Christian theme, I decided to visit the hall of Islamic art, which I had already seen a little in Turkey, in Istanbul, and even at real battle sites of the First World War while tracing the history of the Dardanelles operation.

- Autumn morning September 3

- Glass pyramid – entrance to the Louvre

- Small queue of visitors without a guide

- Escalator, ticket office and museum entrance

- Italian sculptures, Donatello Gallery, Byzantine Empire

- The Descent from the Cross (Late 9th early 10th century)

- The Virgin of the Annunciation (made of polychrome wood)

- Sculptures “Virgin and Child” and Saint Christopher

- Angel candelabra holder (Giovanni della Robbia 1469-1529, Florence)

- Dead Christ (Madrid, first quarter of the 18th century, polychrome wood)

- Northern Europe, Saint Mary Magdalene, 1515-1520

- Christ of Palm Sunday (wood, paint, Swabia 1520-1525)

- Islamic art – ancient dishes, household items (Egypt, Middle East 7th-10th centuries)

- Candlestick with Kufic inscription, jugs, plates, saber (Syria and Türkiye, 12th-15th centuries)

- Tombstones (Umm Muhammad, Muhammad al-Hashimi etc., Egypt, 230-282)

- Stele of Ali al-Jawhari (Egypt, Cairo, 382, marble)

In the “Art of Islam” hall, the history, context, and geography of the artifacts on display are shown on a map with the designation of the areas. I am not an expert on Islamic art, so I can only speak about the exhibits that I liked as an ordinary visitor. I would like to note the jugs and plates with drawings, gilded candlesticks and even a blade with Arabic script. Tombstones are of interest to specialists because they are valuable historical artifacts, replete with names and dates of historical figures and their lives. The next room, “The Art of Burial in Egypt,” seemed more interesting to me, since I had studied it in my school curriculum. The halls contained a large collection of mummies, death masks of historical figures, beautiful tombstones, and even a sarcophagus. Portraits and heads of mummies allow us to better understand the people of that era and how they saw themselves.

After the Egyptian halls there is again a crossroads and a choice on where to continue the tour. I went to the hall of Ancient Greece. Again dishes, jugs, figurines and household items. In the next room, giant amphorae, wine jugs with beautiful designs, and elegant figurines are of particular interest. Women’s busts are replaced by animals, including mythical ones. The maps show the locations where these Greek Hall artifacts were found, including the Greek mainland and the Aegean islands, as well as a brief history of the excavations. (Some were not conducted in ways considered “proper” by archaeologists today. Some even involved dynamite blasting charges!) Several rooms are occupied by fragments of walls with inscriptions in Greek.

Next, my route passed through the halls of “Egypt of the Copts,” where there is a large collection of beautiful color drawings and bas-reliefs. Beautiful figurines and household items are displayed such as hair combs, bracelets, jewelry, jugs and even children’s toys. The Coptic Egypt section occupies several rooms, one of which reproduces a monastery, and the other is dedicated to hand-made textiles and patterned fabrics. The halls also display large-scale models of churches and buildings with figures of people and interiors. The screens show multimedia stories about the Coptic monasteries and archaeological excavations. You can spend half a day in these halls, looking at and studying large-scale models and artifacts, but one hour is enough for a quick initial acquaintance.

Again a crossroads and a choice of path in the direction of Greece with graceful figures from the period from Zeus to Olympus. Scale models and original fragments of the most famous buildings of ancient Greece. The Temple of Zeus, the Pantheon, the Acropolis of Athens and the sculpture of Hercules are classics of history. A rich collection of Greek artifacts occupies several galleries and halls. The most famous exhibit, of course, is the Venus de Milo, next to which there are always many tourists from Europe and China. All visitors want to take a souvenir photo with this famous sculpture. In this hall and its continuation there are less famous, but high artistic level sculptures with a detailed description of the place of discovery and the authors. Aphrodite, Zeus and all the famous Greek heroes are represented in these halls.

In the next room, I remember the gold, silver and bronze coins of the northern Greek principality of Macedon with portraits of the Emperors. Greek sculptures smoothly transform into Italian ones. A whole hall of small bronze figurines by Italian masters, depicting all scenes of life and activity of that period. There is also a collection of jewelry, represented by necklaces, icons, gold rings, earrings and various chains. There are fragments of weapons and armor for warriors. The next room shows beautiful silver kitchen sets – plates, spoons, cups, goblets and other items with artistic decoration.

After the silverware, the tour continues in the Henry II room and the rooms with oil paintings by famous masters. Artists Lawrence, Rubens, Van Dyck, David, Fragonard and other masters are represented here. Then again Greek miniatures and the fourth hall of the Charles X Museum, then the sixth hall. The head has already ceased to perceive information, the examination is carried out fluently. The room itself with artifacts, walls and ceilings with bas-reliefs are the interior of the palace and deserve special attention. Finally I come to the grand gallery of Apollo. The decorations, paintings and bas-reliefs of this hall are a worthy competitor to the Palace of Versailles. The display cases display a unique collection of jewelry from famous personalities. Empress Marie-Louise’s diamond necklace, Princess d’Angouleme’s tiara, her bracelets, royal insignia and even a real crown. The Louvre Museum was closing at this point and the initial inspection ended. I walked quickly, without studying the exhibits, spent almost the whole day, but visited less than 30% of all the halls. On my next visits, I plan to survey the remaining halls, having previously studied the layout of the collections received at the ticket office. I attach a small photo gallery about visiting the Louvre Museum below. I assume the point of this article is to offer the Louvre as a tour destination. If so, you need to portray yourself as an expert on the Louvre even if you really aren’t. I would add a paragraph telling the reader how since your first visit, you have studiously examined the Louvre and its collection, and can provide tour services for those in need. You already mention the value of a guide early in this section, so that is good. (MB, Paris, september 2018)

- The art of burial in Egypt – masks of the elite

- Gravestone paintings on marble

- Painted stucco mummy masks, 1st-2nd century AD

- Sarcophagus with mummy mask

- Greek amphoras of gigantic size (6500 – 500 century BC, Crete)

- Arula, scene of the metamorphosis and battle of Hercules (Greece, 6th century BC)

- Figurines of a woman, an athlete, the head of a sphinx (Greece, 6th century BC, terracotta, bronze)

- General view of one of the Greek halls

- Fragment of a wall with a gladiator’s inscription in Greek (1st-2nd century AD)

- The art of weaving, portrait on tapestry (Egyptian Coptic, 6th century AD)

- Gold jewelry, rings, brooches, pendant ((Egypt, 1st-2nd century AD)

- Textile production, fabrics with patterns

- Scale model of the 6th-8th century church in Baouit (fragments in the hall)

- Bronze Greek figurines of Hercules fighting and Dionysius, god of wine (460 BC)

- Scale model of the sanctuary of Zeus in Olympya

- Ceiling decorations in the transition between the halls and wings of the palace

- Panathenaic procession of heroes and inhabitants of Athens (500-30 BC,plaster )

- The famous Venus de Milo and Chinese tourists

- Traditional photo for memory or selfie with Venus de Milo

- Very beautiful but less famous Aphrodite (2nd century AD, marble, near Rome)

- Venus “vulgar” (160 AD, Marbre de Carrare, Italy)

- Zeus, god of heaven and master of Olympus (480-450 BC)

- Gold and bronze coins of the Kingdom of Macedonia (359-168 BC)

- Figures of Zeus and Hercules fighting, women and others (460 BC)

- Silverware, Boscoreale treasure, Roman villa near Vesuvius (79 AD)

- Ceiling and walls of the Apollo Gallery

- Sculptures and paintings on the ceiling

- Crown with diamonds, tiara, watch that belonged to royalty

- Queen Marie-Amelia jewelry, tiara, necklace, brooch with diamonds

- Large art gallery, paintings by Italian masters

- Giovanni Pietro Rizzoli “The Death of Cleopatra” (1495-1549, Milan)

- Bernardino Luini “Holy Family” (1510-1515)

- Vittore Carpaccio “The predication of Saint Stephen in Jerusalem” (1514)

- Andrea di Bartolo “Crucifixion” (1503, Milan)

- Daniele Ricciarelli (1509-1566) “The Battle of David and Goliath”

- Hall of the Italian painting

- It is impossible to get close to Mona Lisa (Gioconda) by Leonardo da Vinci

- Gallery of French paintings, including large-sized pictures

- Jacques Louis David “Horatia’s oath of warriors to his father” (1784)

*Note. You can look at all types of cars in France in more detail on our Guide to the Car Museum in Reims, Champagne.