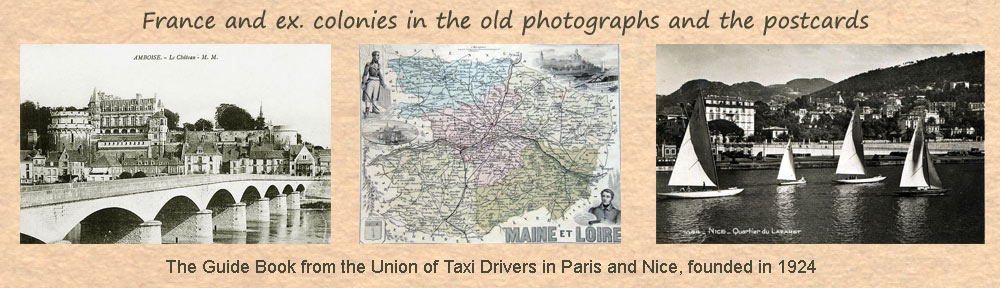

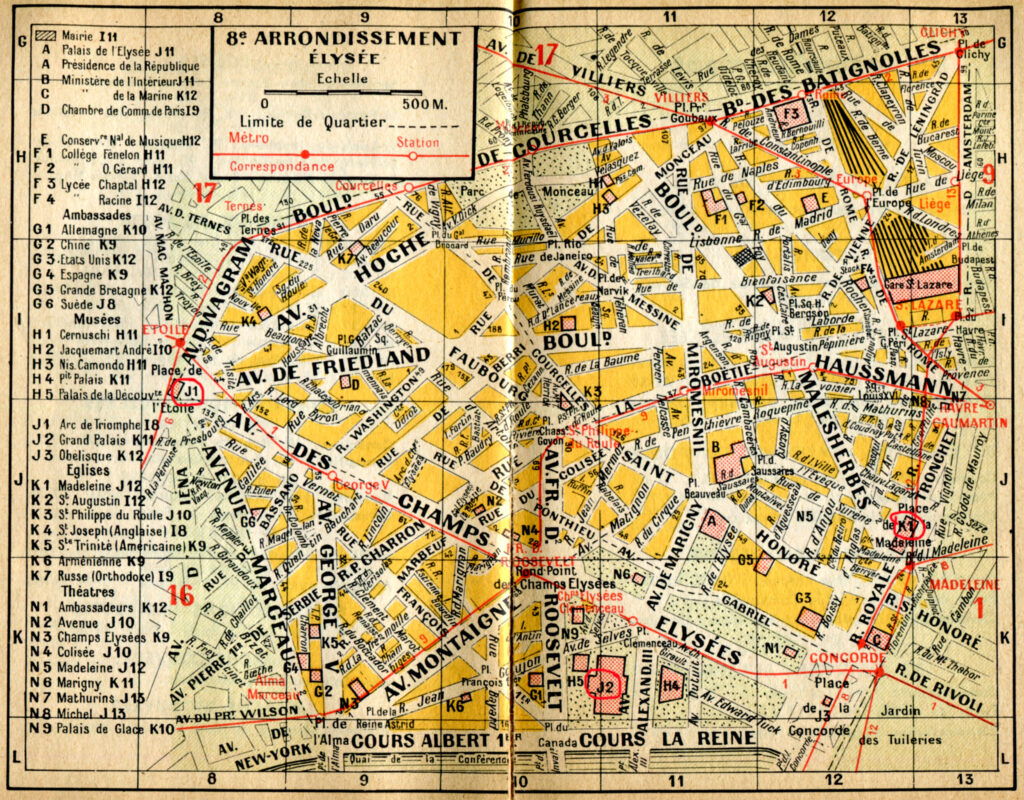

The Arc de Triomphe Paris at the Place de l’Etoile is one of the most famous monuments in France, located at the western end of the Champs Elysées in the center of the Place Charles de Gaulle, formerly the Place de l’Etoile (the “star” of the junction formed by its twelve radiant avenues). The location of the arch and the square is divided between three districts: 16th (south and west), 17th (north) and 8th (east). The Arc de Triomphe honors those who fought and died for France during the Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, with the names of all victories and generals inscribed on its inner and outer surface. Under its base is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of the First World War.

The Arc de Triomphe was designed by Jean Chalgrin in 1806 as the central connecting element of the “Axe Historique” (historical axis, a sequence of monuments and large streets on the route going from the courtyard of the Louvre to the Grand Arch in La Defense). Its iconographic program contrasts heroically naked French youths with bearded German soldiers in chain mail. He set the tone for all public monuments with a triumphant patriotic message.

XIX century, Arc de Triomphe is located on the right bank of the Seine in the center of a dodecagonal figure of twelve diverging avenues. It was built in 1806 after the victory at Austerlitz of Emperor Napoleon at the peak of his triumph. It took two years to build just the foundations, and in 1810, when Napoleon entered Paris from the west with his new bride, the Archduchess Marie-Louise of Austria, he built a wooden model of the completed arch. The architect Jean Chalgrin died in 1811 and Jean-Nicolas Huyot took over the work. Construction was suspended during the Bourbon Restoration and would not be completed until the reign of King Louis Philippe, between 1833 and 1836, by the architects Goust and then Huyot under Héricart de Thury. On December 15, 1840, the remains of Napoleon, brought from St. Helena, passed under it on their way to the emperor’s final resting place in the Les Invalides (Army Museum).

XX century. Interesting Facts. World War I. The sword carried by the Republic in the bas-relief of the Marseillaise broke on the day the Battle of Verdun in 1916 is said to have begun. The relief was immediately covered with a tarpaulin to hide the incident and avoid undesirable ominous interpretations. August 7, 1919 Charles Godefroy (Charles Godefroy) successfully controlled his biplane in flight under the Arch. Jean Navarre was the pilot assigned to make the flight, but he died on 10 July 1919 when he crashed near Villacoublay (Villacoublay Airport) while preparing for the flight.

Military parades. Once built, the Arc de Triomphe became a rallying point for French troops after successful military campaigns and the annual military parade on Bastille Day. The famous victory marches around or under the Arch included the Germans in 1871, the French in 1919, the Germans again in 1940, and again the French and the Allies in 1944 and 1945. arch. in the background as victorious American troops march down the Champs Elysées and American planes fly overhead on August 29, 1944. However, since the burial of the Unknown Soldier, all military parades (including the aforementioned post-1919 one) have avoided marching through the true arch. The route goes up to the arch and then around it, out of respect for the tomb and its symbolism. Even Hitler in 1940, like de Gaulle in 1944, observed this custom.

- Arc de Triomphe in Paris before World War I

- Tanks on military parade Victory day

- French tanks on the Champs Elysees in Paris

Monument building. The astilar was designed by Jean Chalgrin (1739–1811) in a neoclassical version of ancient Roman architecture. The Arc de Triomphe sculpture features the country’s largest academic sculptors: Jean-Pierre Cortot; Francois Rude; Antoine Etex; James Pradier and Philippe Joseph Henri Lemaire The main sculptures are not solid friezes, but are seen as independent trophies applied to huge masses of hewn stonework, in contrast to the gilt-bronze appliqués on Empire style furniture. The four sculptural groups at the base of the Arch are the 1810 Triumph (Cortot), the Resistance and the Peace (both works by Antoine Etex) and the most famous of these is the 1792 Departure of the Volunteers, commonly called the Marseillaise (Francois Rude). The face of an allegorical depiction of France calling its people at the last was used as a belt buckle to confer the honorary title of marshal. After the fall of Napoleon (1815), the Peace sculpture is interpreted as commemorating the Peace of 1815.

In the attic above the richly sculpted warrior frieze, there are 30 shields engraved with the names of major victories during the French Revolution and the Napoleonic Wars. On the inner walls of the monument are the names of 660 people, including 558 generals of the First French Empire. The names of generals who died in action are underlined. The shorter sides of the four supporting columns are also engraved with the names of major victories in the Napoleonic Wars. Battles that took place between Napoleon’s withdrawal from Elba and his final defeat at Waterloo are not included.

For four years, from 1882 to 1886, a monumental sculpture by Alexandre Falguière crowned the arch. Titled “The Triumph of the Revolution”, it depicted a horse-drawn chariot preparing to “crush anarchy and despotism”. She stayed there for only four years before being destroyed. Inside the monument, in February 2007, a permanent exhibition was opened, conceived by artist Maurice Benayoun and architect Christophe Girault. The steel and new media installation questions the symbolism of the national monument, questioning the balance of its symbolic message over the past two centuries, oscillating between war and peace.

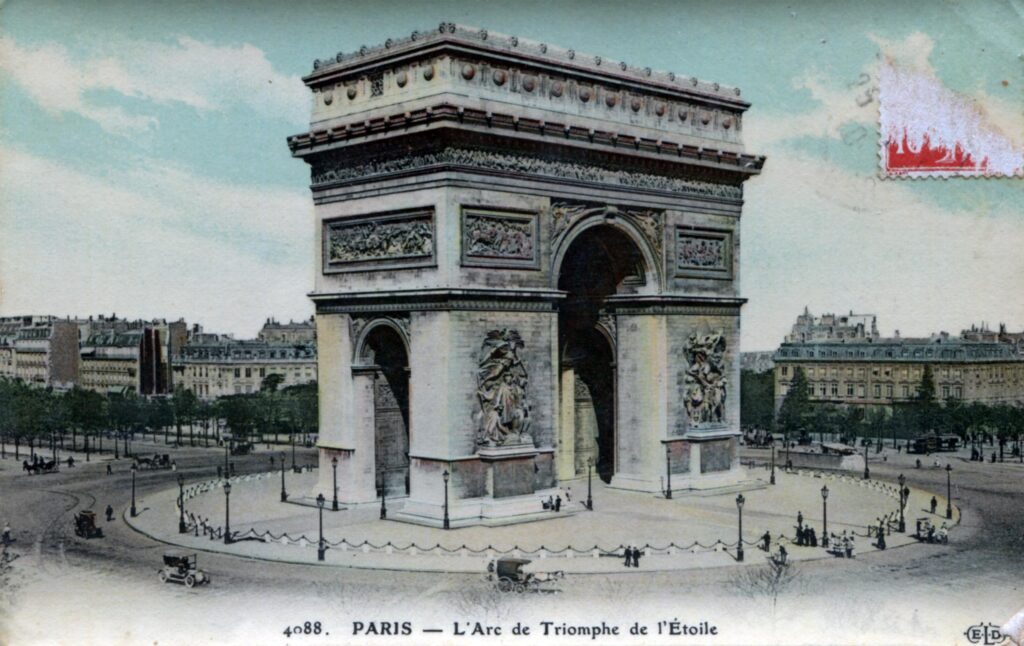

- Photo 1 (Sightseeing tour of Paris)

- N2 from south

- N3 from Concorde square

Tomb of the Unknown Soldier

Beneath the arch is the Tomb of the Unknown Soldier of World War I, buried on Armistice Day 1920, which lit the first eternal flame in Western and Eastern Europe since the fire was extinguished in the fourth century. It burns in the memory of the dead who were never identified (now in both world wars).

A ceremony is held at the Tomb every November 11 on the anniversary of the November 11 armistice signed by the Entente powers and Germany in 1918. Initially, on November 12, 1919, it was decided to bury the remains of an unknown warrior in the Pantheon, but a public letter-writing campaign led to the decision to bury him under triumphal arch. The coffin was placed in the chapel on the first floor of the Arch on November 10, 1920, and placed in its final resting place on January 28, 1921. On the top of the slab is the inscription “ICI REPOSE UN SOLDAT FRANÇAIS MORT POUR LA PATRIE 1914-1918” (“Here lies a French soldier who died for the fatherland in 1914–1918).

Russian trace. The Russian Empire*, unlike the USSR, was an equal member of the coalition of the Entente countries and had every right to the ceremony of lighting the fire. This tradition belongs to and is observed by the veteran organizations of the Russian Imperial Army, including the Cossacks, the Expeditionary Force and the Legion of Honor. Once a year, members of these émigré organizations participate in the Lighting of the Fire ritual.

* The Russian Empire, which was destroyed in 1917, included Russians, Ukrainians, Belarusians, Poles, Georgians and other peoples.